Ireland 1913 – 1921: The Bureau of Military History Collection

Historical research has been transformed in recent years by the sheer amount of material now easily accessible online. One such valuable resource is The Bureau of Military History (BMH) Collection. Orla from Malahide Library takes us through some highlights of the collection.

The BMH is a treasure trove of 1,773 witness statements, 334 sets of contemporary documents and 42 sets of photographs relating to the revolutionary period in Ireland between 1913 and 1921. This material was collected by the State between 1947 and 1957 when BMH staff, including army officers, civil servants and interviewing officers, travelled throughout Ireland interviewing survivors of the period. It was only in 2003 that this collection was released into the public domain. In 2012, a substantial portion of the materials was made available online, giving anyone interested in this period of Irish history easy access to the collection.

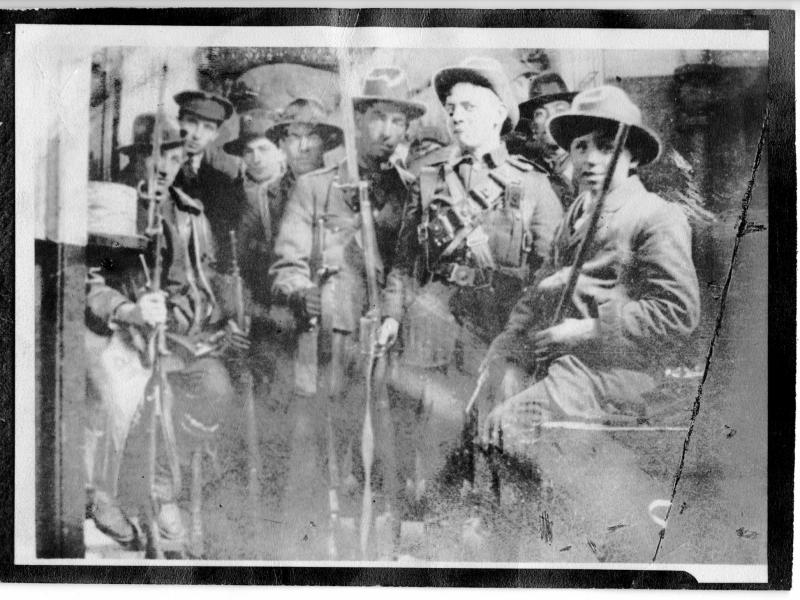

This BMH Photo series consists of 400 photographs, many of which are instantly recognisable images of the period such as the arrest in 1913 of a disguised Jim Larkin and Countess Markievicz in I.C.A. uniform, as well as less familiar images. Letters, memos, rare publications, pamphlets, drill manuals and posters feature among the 2,500 contemporary documents in the collection. By clicking on any one of the 12 embedded voice recordings on the BMH website, you can hear figures from Irish history, including Maud Gonne McBride and Kathleen Clarke, tell their stories in their own words.

The centrepiece of the collection is the 1,773 witness statements. These engrossing first-person accounts give fascinating insights into the early 20th century revolutionary period in Ireland.

One of the statements is by Nora Ashe, sister of Thomas Ashe, the commander of the Fingal Battalion of Irish Volunteers who died on hunger strike in Mountjoy Prison in 1917. She recalls that her brother “had a set of bagpipes and used to go up on Kinnard hill which belonged to our farm and walk along it, playing the pipes. The neighbours all over the parish used to love to listen to the music and missed it greatly when he was dead. He had a beautiful voice, both for speaking and singing and a wonderful collection of ballads and songs”.

Lily Mernin, a shorthand typist who worked in Dublin Castle, became an intelligence agent for Michel Collins during the War of Independence, passing on information from within the very seat on British rule. When suspicions were raised about how Collins was obtaining this information, she recalls: “I found myself in a predicament, but I remained cool and calm and bluffed my way out of it and said: ‘Who could be a spy?’”

Eugene Bratton, an RIC constable in Meath, notes that “when the Truce came, the officers of the R.I.C. were almost crying. They realised that their good days were over and they had good days before the trouble began. They were kings in their own areas. The ordinary rank and file of the R.I.C. were generally pleased that Ireland at last had succeeded in getting somewhere. As far as the Black and Tans ware concerned, they did not give a damn, they were soldiers of fortune”.

Browsing through and searching the BMH Collection brings many such stories to light. The Bureau of Military History Collection can be accessed at: < www.militaryarchives.ie/collections/online-collections/bureau-of-military-history-1913-1921 >

Orla, Malahide Library

(Photo caption: Group of Irish Volunteers and one member of the I.C.A. inside the G.P.O. Dublin, Easter Week. 1916. From the BMH Photo Series)