25th Anniversary Series Blog 2

25th Anniversary Series Blog 2

1700s – Ireland’s First Public Library

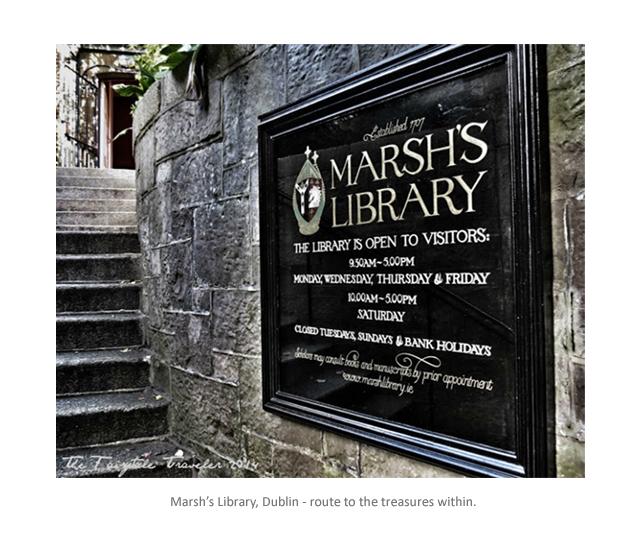

In the heart of old medieval Dublin, proudly stands the immense 800-year-old Gothic structure that is St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Its lofty spire pierces the sky, its looming shadows cast so wide as to extend unapologetically beyond the perimeter of its grounds, its presence is so stark and obvious, one would almost be led to believe there was little else of interest in the area. Yet, hidden amongst the shadows of this mighty structure is an almost secret, diminutive gem, its value to Dublin’s heritage equally as impressive as that of its neighbour – Marsh’s Library, Ireland’s first public library.

Marsh’s Library - 1707

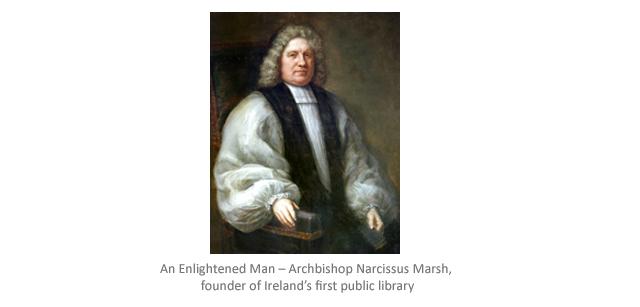

In 1701, Archbishop Narcissus Marsh, a devout clergyman and scholar, and of British origin, contributed to Irish scholarship in a way which cannot be understated. Three years previous, having been offered and accepted the Provostship of Trinity College Dublin, finding his time and duties rather troublesome, he wrote in his diary: ‘the ill education that the young scholars have before they come to College, whereby they are both rude and ignorant; I was quickly weary of 340 young men and boys in this lewd and debauched town’(1).

As a person of the Enlightenment era, Marsh felt strongly about the importance of reading and researching extensively. Whilst provost of Trinity, Marsh was astounded to discover, under the statutes of the college, it was not open to the public. He was equally appalled by the restrictions imposed on students using the library at Trinity College. Shocked there was no accommodation in the capital for the public to go and read, in 1700 he wrote to his friend, Dr. Thomas Smith of London, a distinguished scholar and book collector, ‘twas this, and this consideration alone that first moved me to think of building a library in some other place for public use, where all might have free access’(2). These words were to bestow upon the capital a gift and legacy of which to be proud.

Marsh set aside £800 to build the library, and he bequeathed his personal collection of books to the library upon his death. In a letter to Dr. Smith he explained his reason for doing so was because he had ‘no relation that I think deserves such a favour’ (3).

Marsh’s Parliamentary Act & Opposition

Having built and then furnished the library with the finest works of the Renaissance era, Marsh was anxious to have the library and its government incorporated into an act of parliament. The Act, drafted by Marsh himself, was called ‘An Act for Settling and Preserving a Public Library for ever’. The Act vested the house and books in a number of clerical and legal officers of the state, and their successors, as Governors and Guardians of the Library. Curiously, there existed some opposition to this Act, which Marsh believed was of a personal nature and by, as he described, ‘men of my own coat’. The four opposing bishops described the Library Act as containing ‘simony, sacrilege and perjury’(1). Further opposition arose from another quarter – one of the leaders of which was Jonathan Swift who had been elected as Proctor to represent St. Patrick’s Cathedral in the lower House of Convocation. Swift agreed, for similar reasons, with the clergy that Marsh’s Library Bill was dangerous. Fortunately, the opposition was withdrawn and the library was formally incorporated in 1707, exempting the building ‘forever from all manner of taxes such as chimney money, hearth money, and lamp money, and from all manner of taxes or charges hereafter to be imposed by Act of Parliament’(1).

Marsh’s Extraordinary Collections

The library cost Marsh £5,000, much of which was spent consciously acquiring some wondrous and widely sought-after collections of which to stock the shelves. There are 25,000 books in Marsh’s Library and there are four main collections.

The first major collection was purchased by Marsh in 1705 – the library of the late Bishop Edward Stillingfleet who had been Dean of St. Paul’s, London, one of the best preachers and writers of his day. This collection contained about 10,000 books and cost £2,500 to purchase. The Stillingfleet collection was regarded as the best private library in England. The range of subjects covered include theology, history, classics, law, medicine and travel.

The second collection belonged to Frenchman Dr Elias Bouhéreau, who left 2,000 books to Marsh’s in 1701. This collection relates to seventeenth-century French religious controversies and the study of Calvinism France. It contains books on medicine which was Bouhéreau’s profession in La Rochelle.

The third collection is that of Marsh’s own library which he donated. Marsh’s donation extended the collection with Arabic and Hebrew books, as well as oriental material.

The Bishop of Clogher, John Stearne, bequeathed his books to the library in 1745. Stearne is the only major Irish collector represented in the Library and a considerable part of his collection relates to Ireland (2).

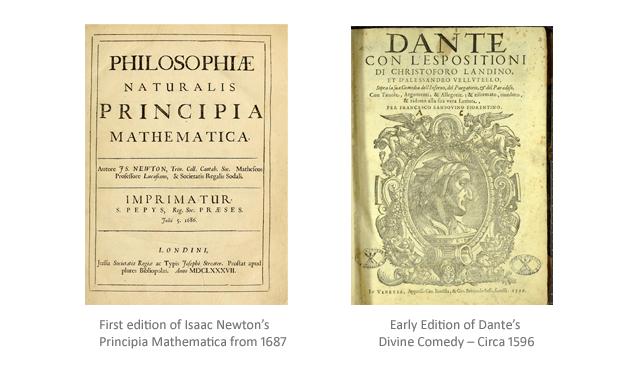

There are many prized treasures amongst the collections at Marsh’s. One very book – a rare and valuable possession of great interest – the first edition of Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica from 1687. Another rarity is an early edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy (2).

Ireland’s First Public Librarian

The aforementioned Dr Bouhéreau left his expansive library collection to Marsh’s as a condition of his appointment as first administrator of the Library by Marsh. Bouhéreau, a prosperous, well-read, and well-connected physician and church elder based in La Rochelle, France, was a Huguenot refugee to England. He was secretary to Henri de Massue de Ruvigny, who later became Earl of Galway. It was thus that he became known to Marsh, who appointed him first Library Keeper at £200 per annum; as such, Bouhéreau became the first public librarian in Ireland (1)(3).

Irish Language Revival

Marsh was involved in drafting the Penal Laws which penalised the practice of the Roman Catholic religion and imposed civil restrictions on Catholics, as well as Protestant dissenters. However, in a peculiar move, Marsh, who noticed while at Trinity College that thirty of the seventy scholars chosen every year whom had to be, by statute, Irish natives, could all speak Irish, though none could read or write the language. Marsh, moved by his academic passions and devotion to the cloth, and at his own expense, employed a former Catholic priest to teach Irish reading and writing skills to the students and to preach a Protestant sermon in Irish once a month.

Although Marsh’s only concern was the ability to instruct students in the Protestant faith, his act may be appreciated, retrospectively speaking, as an unwitting but crucial step in the relationship between public libraries and the revival of the Irish Language and Irish Culture, which would continue for centuries to come (1)(2).

Thieves & Cages

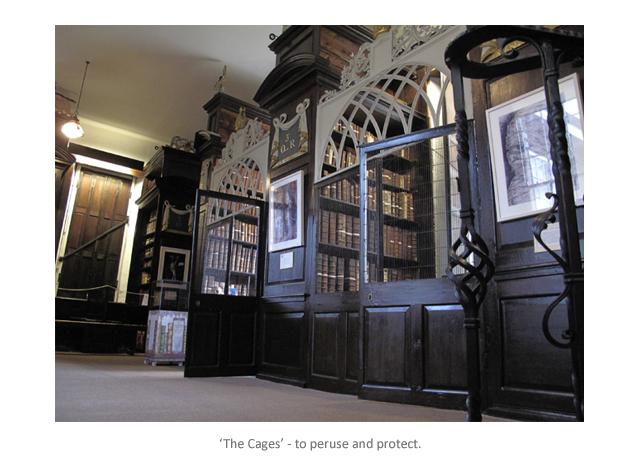

Marsh’s Library’s demure exterior structure exists in stark contrast to its ominous, obsidian-black – and yet scholarly – interior. Designed by Sir William Robinson, Surveyor General of Ireland, it is based, on the instruction of Marsh, on the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Marsh’s Library boasts majestic dark-oak bookcases, each with a carved and lettered gable, topped by a mitre. The ambience is one of an almost foreboding nature. These shadowy environs greatly aided the nimble hands of thieves, who had unfettered access to numerous prized works. To combat this problem, Marsh instructed, as a security

measure, the construction of ‘the cages’ – three ornate, wired alcoves at the end of the second gallery, in which readers were cautiously locked when perusing smaller, rare and more valuable books under the watchful eye of the library keeper (1)(3).

Dublin’s Literary Lights – Stoker/Swift/Joyce

For 150 years, Marsh’s Library remained the only library available for public use in Dublin. In the eighteenth and nineteenth century it enticed some fascinating readers and visitors. Inscribed in its ledger are the signatures of many a recognisable figure of Dublin’s fine literary pool.

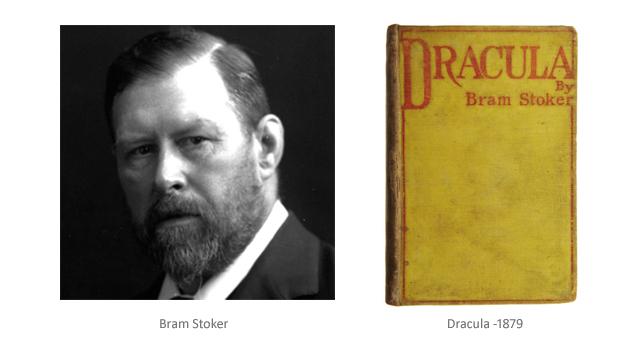

While a student at Trinity College in 1866, Bram Stoker visited the library several times. At Marsh’s, Stoker immersed himself in books on subjects such as travel, geographies, books of a theological nature, and the poetry of Spencer, Dryden, Chaucer and Ben Jonson. The log reveals he took out books on Irish History, Folklore and European Countries, some of which mention Transylvania. It is tempting to conjecture that it was amongst the auspicious stacks of Marsh’s, Stoker began writing his Gothic horror ‘Dracula’, or at the very least was inspired by the offerings of his finds (2).

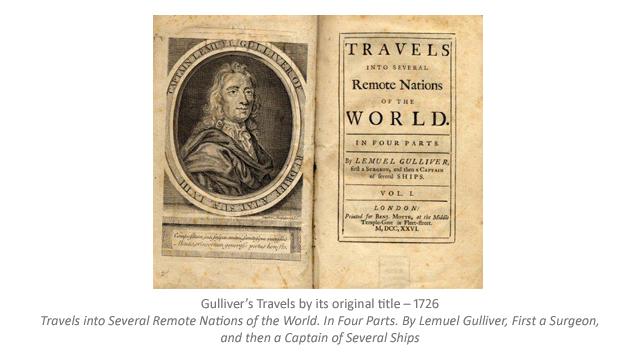

Despite his initial opposition to Marsh’s Library, inked entries in the visitor’s ledger prove the turnabout of Jonathan Swift, most famed as the author of Gulliver’s Travels. In fact, the Swift Case displays printed works of the satirical fantasist, as well as his plaster death mask. And so his presence remains to this very day in the library he once so vigorously opposed (2)(3).

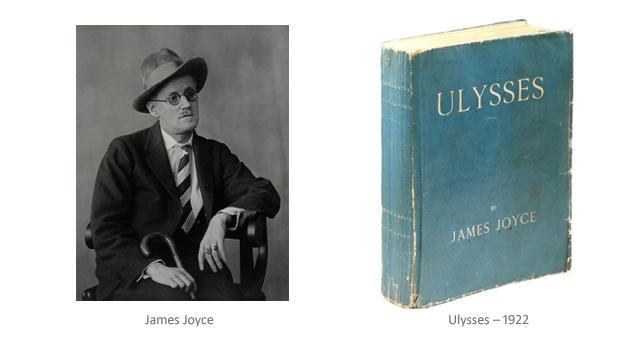

‘…Beauty is not there. Nor in the stagnant bay of Marsh’s Library where you read the fading prophecies of Joachim Abbas’ – James Joyce’s direct homage to Marsh’s Library, where he came to study the 16th-century book The Prophesies of Joachim Abbas, as in his gloried book Ulysses (2).

Vampires & Ghosts

Alluring as it is to suspect Marsh’s Library may well have given rise to one of horror’s most infamous and darkest creatures – Dracula – the mythological creature is not the only one of its kind to stake claim to these grounds.

While serving as Archbishop, Marsh assumed the care of his nineteen-year-old-niece, Grace, who, in turn, took on the task of housekeeping. Not appreciating the strict code of conduct set in place by her uncle, one evening Grace eloped to be with her partner. Before doing so, she penned a letter to her uncle, apologising and explaining the need for her course of action. She placed the letter in an open book Marsh had been reading that evening in his study. By a terrible turn of events, Marsh did not resume reading the book, instead returning it to the shelves, the letter hidden within its pages. Marsh died years later, never having read the words of his niece.

And so it is told that the ghost of Archbishop Marsh haunts the galleries of his library in search of the unread letter from his niece (2).

Now as it Was Then

Though Marsh’s Library is intended for public use, its appeal, though great, was limiting and favoured by scholars. However, this was just as its creator envisioned, as Marsh anticipated his library for the use of graduates and gentlemen. Nevertheless, the library experienced high levels of visitation. In the Post Office Directory for Dublin in 1860, Marsh’s Library is listed as the Public Library of Dublin, with the number of readers ranging from 1,200 to 1,500 annually. The directory guides us in the era’s rules of engagement:

‘Readers are admitted gratuitously and without any religious distinction, the only request being a satisfactory certificate of respectability and good character.’

Marsh’s Library has remained virtually unchanged for more than 300 years. It is an outstanding example of a 17th-century scholars’ library and is one of the few 18th-century buildings in Dublin still being used for its original purpose (1)(2).

By Laura Flanagan, Fingal Libraries

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Next Monday, July 15th: Repeal Rooms, Public Library v Public House, Literary Revival and much more!

We hope you join us!

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

For your interest:

Fingal Libraries Local Studies and Archives is a repository of photographs and documents, private and donated collections, encapsulating visual and literary snapshots of Fingal and the Dublin area through history.

It is a treasure trove for anyone looking to unearth the rich culture and heritage that is the region of Fingal. Staff are exceptionally knowledgeable and always willing to help in your research.

Thanks to Catherine, Brian and Karen for allowing access to archives for this blog series.

Research material used in the blog series can be found through the Encore catalogue on Libraries Ireland website:

University of the People: celebrating Ireland’s public libraries: the Thomas Davis lectures 2002. An Chomhairle Leabharlanna. 2003 Call No. 027.4415

Public libraries in the 21st century: defining services and debating the future / Anne Goulding. 2006. Call No. 027.44

A history of literacy and libraries in Ireland: the long traced pedigree / Mary Casteleyn. 1984. Call No. 027.0415 Ireland

Irish Carnegie Libraries : A Catalogue and Architectural History / Grimes, Brendan. 1998. Call No. 027.4415

Dublin Libraries : A Pictorial Record / Lennon, Sean. 2001. Call No. 027.0418

Another invaluable resource during research included the Irish Newspaper Archive, available for use on public PCs at your local Fingal Library.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

(1) A history of literacy and libraries in Ireland: the long traced pedigree / Mary Casteleyn. 1984.

(2) McCarthy M. Narcissus Marsh and his Library. Early Modern History (1500-1700), Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 1996), Volume 4.

(3) McCarthy M, Archbishop Marsh and the First Public Library in Ireland. In : McDermott N. (ed) The University of the People: celebrating Ireland’s public libraries: the Thomas Davis lectures 2002. Dublin: An Chomhairle Leabharlanna; 2003. p.1-11.