Colmcille in Swords

It is said that when Saint Colmcille was in Swords that he wanted water. He took a step from the round tower to the place where the well is and where his foot rested a well sprang up. This step would be about three hundred yards.

(SC 0789: 155; SC 0788: 124; SC 0789: 153).

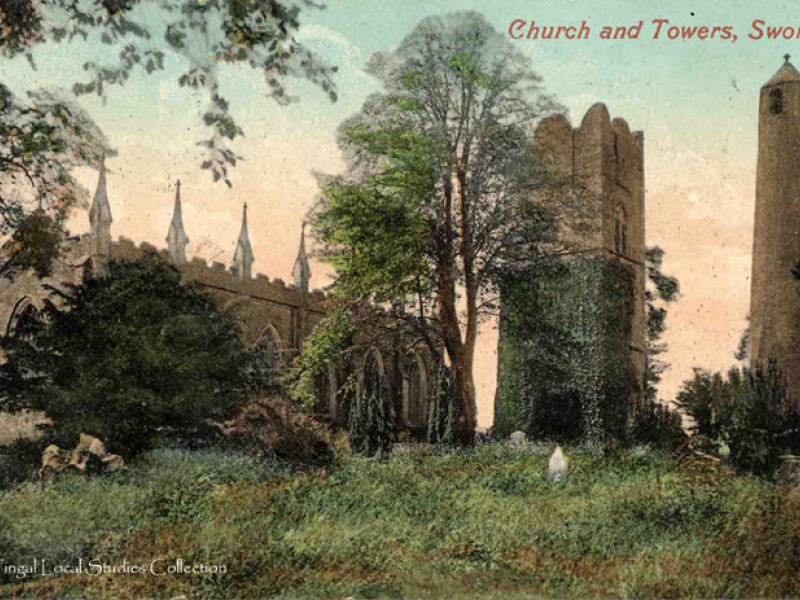

Colmcille is also associated with the round tower in Swords and according to some local stories is credited with building both the church and round tower[1].

The Well and the Church

The church and round tower sit on an elevated site and are visible from many points within Swords village. It has been suggested that the curving alignments of the Brackenstown, Church and Rathbeale roads preserves the original extent of the enclosing boundary of the monastic site[2]. However, the west tower of the church is the only medieval element which survives today. Colmcille’s well sits below but within view of church and was traditionally visited to cure sore eyes. According to local tradition Swords (Sord in Irish meaning pure or clear) comes from the well itself[3]. However, one local story attributes the founding and naming of the Swords or Sord Colmcille to the saint[4]. As Colmcille is associated with the creation of the well from which springs the name of Swords both may be central to the foundation and identity of this place.

[1] (Archer 1975: 19-24; SC 0789: 150; SC 0783: 72).

[2] (DU00402, Baker 2015).

[3] (Branigan 2012: 60; Skyvova 2004: 66).

[4] (SC 0792: 212).

Who was Colmcille?

Our earliest written evidence for St. Colmcille (or St Columba as he is sometimes called) comes from medieval biographies written by two abbots of Iona called Adamnan and Uimíne Ailbhe[1]. According to these biographies, Colmcille was born in Donegal in the 6th century and went to study at Clonard under St. Finnian afterwards founding several monasteries in Ireland. Supposedly he copied one of St. Finnian’s gospels without permission and was ordered to return the copy by order of king Cormac Mac Art[2]. Colmcille refused and went on to fight a bloody battle over the manuscript at the foot of Benbulben. Interestingly, Colmcille was supposed to have been the great grandson of Conall Gulban, who was named for Benbulben giving the saint several links to the Sligo landscape[3]. This dispute is sometimes cited as the first recorded copyright dispute! After losing the battle he was exiled to the Hebridean Island of Iona where his adventures continued. He is credited with both the banishment of the Loch Ness Monster and with the establishment of Celtic Christian monasteries in Scotland[4]. Indeed, the cille element of his name means church and the establishment of monasteries and church sites seems to be of central importance to Colmcille.

Want to Delve Deeper?

If you want to find out more about the life and times of Colmcille visit CELT.ie to access Adamnan’s biography of the saint. If you’d like to explore more of the folkloric traditions about Colmcille visit Dúchas.ie. If you'd prefer to learn more about medieval archaeology in your area visit the National Monuments Environment Viewer here. Or why not enjoy an in person visit to the well and the church in Swords!

- Aoife Walshe

Bibliography

Adamnan, The Life of Columba, trans: Reeves, William, accessed through https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T201040/index.html.

Archer, Patrick (1975), Fair Fingall, Dublin.

Columba, St. (2011). In L. Rodger, & J. Bakewell, Chambers Biographical Dictionary (9th ed.). Chambers Harrap. Credo Reference: https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/chambbd/columba_st/0?institutionId=913

O hOgain, Daithi (1991), Myth Legend and Romance, England.

DU00402, National Monuments Record, Compliers: Baker, Christine; Stout, Geraldine (2015), accessed through http://map.geohive.ie/mapviewer.html.

DU00404, National Monuments Record, Compliers: Baker, Christine; Stout, Geraldine (2015), accessed through http://map.geohive.ie/mapviewer.html.

DU00413, National Monuments Record, Compliers: Baker, Christine; Stout, Geraldine (2015), accessed through http://map.geohive.ie/mapviewer.html.

School’s Collection, National Folklore Collection, accessed through www.Dúchas.ie

[1] (O hOgain 1991: 92).

[2] (O hOgain 1991: 94).

[3] (O hOgain 1991: 107).

[4] (Rodger & Bakewell 2011).