The Eye and the Head

Both Howth and Ireland’s Eye are Norse names that identify past Viking interaction with these places. The word Howth comes from the Danish word hoved meaning ‘head’ while Ireland’s Eye comes from Eria’s -ey . Ey is a Norse word for island and is reflected in other island placenames such as Lamb-ey or Lambay as it is called today. However, before Norse influence at these places both Howth and Ireland’s Eye were known by other names.

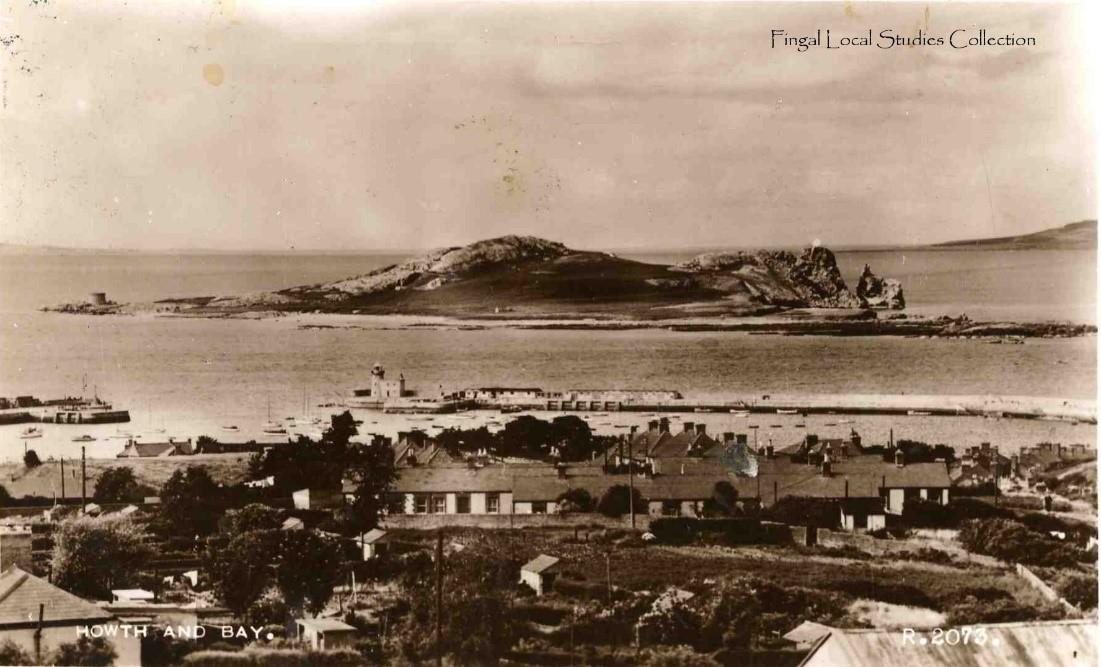

Ireland’s Eye

The Irish name for Ireland’s eye is Inis Mac Nessan which means the island of the sons of Nessan. St. Nessan was a patron saint of Howth who was supposed to have been a member of one of the ruling dynasties of Leinsteir . According to local tradition St. Nessan founded a church on Ireland’s Eye . He was also supposed to have split a rock (called ‘Devil’s Rock’) after flinging a book he had been reading at the devil who was sitting on the rock. However, in some traditions it is the sons of Nessan who built the church and indeed the island seems to have been named for them rather than Nessan himself . A pre-Norman church dedicated to St. Nessan did exist on the island and the ruins of the structure can still be found there today. Interestingly an illuminated manuscript from the seventh century known as ‘The Garland of Howth’ associated with St. Nessan was said to have been deposited in this church. The manuscript is today housed in the library of Trinity College Dublin and more details about this can be found below.

The placenames database of Ireland gives Inis Faithlenn and Inis Eireann as alternative names for Ireland’s Eye. Inis Faithlenn seems to mean grassy island while Inis Eireann comes from Inis Eria meaning the island of Eria. The name Eria may have become confused with the word Erin leading to the island being called Erin’s ey by Norse people. However, it should be noted that Ireland’s Eye has been linked to a place lore poem called Benn Codail in which Codal rears a woman called Erin who goes on to become a guardian of the King of Tara . The name Erin comes from Érna an ancient tribal name from which the name Ériu for the whole country is derived. Érna may also be a grammatical form of íarn meaning iron a most appropriate material to use while guarding a king!

Howth

Anyone that uses the DART will be familiar with the Irish name for Howth as Binn Édair which means the peak of Édar . Local tradition varies on who this Édar was with some accounts recording him as a chieftain while others suggest a princess or even a Fenian warrior. Two place lore poems preserved in medieval manuscripts record the name of the Hill of Howth as Bend Etair. The first poem describes Etar as a male warrior whose wife is named Mairg (or woe in Irish) . In this poem Bend Etair is named from Etar whose ‘’grave overlooks the water’’ . The poem then goes on to recite various battles and events which took place there. In the second poem Etar is given as the wife of king Frému who died of grief for a man called Gand ‘’she died, the softly-bright active, wife of the steadfast king of Fremu. Hence is named noble Etar’’ . This same poem goes on to describe Etar as the son of Etgaeth who died of grief for a woman named Aine. Yet another poem records that Etar was the wife of Gann:

1. Five wives did Dela's five sons bring hither with hardship: two of them were famous Cnucha and bright radiant Etar.

2. Now Cnucha died here on the hill that is called Cnucha; Etar, wife of renowned Gann, died in the same hour on Benn Etair.

3. Hence is named noble Etar, and Cnucha, populous with hundreds

(Cnucha I)

Although the poetic tradition gives several different versions of how the hill gained its name, they all agree that it was named for a person called Etar who was associated with grief. It is interesting to note that the Hill of Howth, Binn Édaír itself has several cairns and burial mounds located on elevated sites. There is also a portal tomb (now partially collapsed) located beside muck rock on the Deer Park golf course close to Howth castle. The tomb is known locally as Aideen’s grave and according to an antiquarian poem:

Aideen, daughter of Angus of Ben-Edar (now the Hill of Howth), died of grief for the loss of her husband, Oscar, son of Ossian, who was slain at the battle of Gavra (Gowra, near Tara in Meath)

(Ferguson 1864)

Aideen (or Etáin in Irish) is recorded as the daughter of an Ulster champion called Etar in medieval manuscript sources and is here recorded as dying of grief like the various Etars listed above. The theme of grief for reasons now lost to us seems to have been an intrinsic part of the story tradition surrounding Howth.

Want to Delve Deeper?

If you are interested in learning more about the manuscript known as the Garland of Howth, click here. If you want to find out more about the archaeology of Howth, click here to look at the research and fieldwork undertaken by the Resurrecting Monuments community archaeology group. If you feel like enjoying the good weather instead of reading, then why not take a field trip to Howth this weekend?

- Aoife Walshe

Bibliography

Archer, Patrick (1975), Fair Fingall.

Bend Etair I, The Metrical Dindshenchas, trans: Gwynn, E., accessed through https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T106500C/index.html

Bend Etair II, The Metrical Dindshenchas, trans: Gwynn, E., accessed through https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T106500C/index.html

Benn Codail, The Metrical Dindshenchas, trans: Gwynn, E., accessed through https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T106500D/index.html

Burnell, Tom (2006), The Anglicized Words of Irish Placenames, Dublin.

Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language accessed through http://www.dil.ie/

Ferguson, Alex (1846), Aideen’s Grave, accessed through https://celt.ucc.ie//published/E860001-002/index.html.

National Monuments Records (NMR), accessed through https://maps.archaeology.ie/HistoricEnvironment/

O hOgain, Daithi (1991), Myth, Legend and Romance: An Encyclopedia of the Irish Folk Tradition, England.

Placenames Database of Ireland, accessed through https://www.logainm.ie/en/.

Resurrecting Monuments (2019), A Guide to the Archaeology of Howth Peninsula: The Story of Howth and its People, Dublin.

Schools’ Manuscript Collection (SC), accessed through https://www.duchas.ie/en.

The Wooing of Étaín, trans: Bergin, Osborne; Best R.I., accessed through https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T300012.html.