The Mysterious St. Marnock

According to local tradition Portmarnock is named after its patron saint Marnock:

There was a great Saint named Marnóg living on Lambay island. He had a little boat and he used to come over to the [place] which is now called Portmarnock. He had a little place for landing on [...] and the people called it Port. When families came to live in the place, they called it Port-Marnóg. The word Port means a place for landing or a port.

(SC Vol. 0792: 217)

This account is bolstered by historic texts which record that St. Marnock came to Portmarnock in the 6th century[1]. The name Marnóg or Marnock is a condensed form of ‘’Mo-Ernin-Occ’’ which affectionately means my little Ernan or Ernin[2]. Many figures both male and female within manuscript and folkloric sources bear the name Ernan or Ernin. The History of Ireland mentions an Eirnin as the mother of Fodla, Banba and Eriú[3]. While the medieval Book of Leinsteir describes Ernan as the son of a Coluim Ruit[4]. In the medieval Life of Colman, Ernan and Cronan were two sons of Luachan who went to live in a church made of yew on Slieve Bloom[5]. While within folkloric sources Ernan appears as a physician with miraculous healing abilities, as the founder of a monastery in Killernan and as the abbot of a monastery in Drimholme[6]. There is also a St. Ernan associated with Rathnew in Wicklow as well as an Eirnin connected to the monastery of Clonmacnoise[7].

St. Marnock

So, who was St. Marnock, and can he be identified with any of the multitude of Ernans and Ernins listed above? Records held by the placenames database of Ireland suggest St. Marnock of Portmarnock may have been the same as the St. Ernan of Rathnew in Wicklow[8]. Local scholarship suggests St. Marnock can be identified with the Eirnin connected to the monastery of Clonmacnoise[9]. This connection seems to stem from St. Marnock’s association with St. Colmcille. According to local tradition St. Colmcille founded several monasteries within Fingal including a church on Rechru (Lambay) Island[10]. The local tradition in Portmarnock suggests St. Marnock came from Lambay while in the Book of Leinsteir Ernan is the son of a figure called Coluim[11]. A medieval biography of St. Colmcille records that the saint and a young boy called Ernán encountered each other at the monastery of Clonmacnoise resulting in Colmcille making a prophecy about Ernán[12]. While the nature of the connections between Marnock and Colmcille are murky they do indicate a shared story tradition linking the saints within the context of the Fingal coastline.

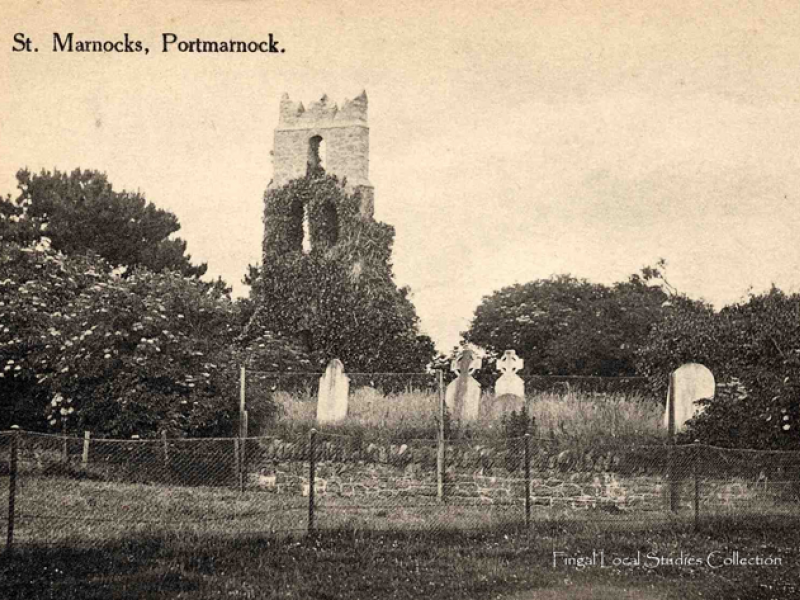

The Church and the Well

St. Marnock not only contributed to the naming of Portmarnock, but he is also supposed to have founded a church there. This church known as St. Marnock’s church can be found through a lane way off Strand Road, south of Portmarnock golf club. There was also once a holy well associated with Marnock here which some have speculated could predate both saint and church[13]. According to local tradition the well had a flight of sixteen stone steps leading down to it and on its north side grew a willow tree which dipped into the water:

There is a holy well in Portmarnock which is in the parish of Baldoyle. It is situated in Saint Marnock's graveyard. It was founded by Saint Mar-nock in the fourteenth century. People in olden days visited and said prayers at the well. Many people were cured of very serious diseases by drinking the water or by bathing in it. Rounds of the stations at one time were performed at the well. It is said that long ago every night a branch of a tree which grew beside the well would bend over it and that at sunrise every morning it would rise again. People were only cured if the water touched the affected part or if they drank it immediately after the branch of the tree arose. I often visited this well, but it is not used for curing diseases now.

(SC Vol 0792: 130)

This willow tree was venerated by fishing folk due to a belief that it could predict storms[14]. A horde of silver coins from the reign of Henry V, Henry VI and Edward IV were found at the site and may have been votive offerings removed from the well and hidden[15]. An ogham stone which was thought to bear the fingerprints of St. Marnock used to stand beside the well until a local landowner had it broken up, mixed with mortar, and incorporated into the masonry of the well which he filled in[16]. Up until the 1940s a section of the Ogham stone was still visible at the well and was known locally as the ‘writing stone’[17]. A pump was erected over the filled in well which functioned as a cattle trough until the 1970s [18]. However, the good news is a Rr. John Shearman rescued some of the stone’s fragments and made copies of the markings which are now held by the Royal Irish Academy library.

Want to Delve Deeper?

If you're interested in learning more about the lore surrounding St. Marnock and St. Ernan visit Celt.ie and Dúchas.ie. If you prefer to be out in the summer air, I recommend a visit to the church site of the mysterious St. Marnock followed by a walk on the beautiful Velvet Strand!

- Aoife Walshe.

Bibliography

Adaman, The Life of Columba, trans: Reeves, William, accessed through https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T201040/index.html.

Ahern, Garry (2013), Portmarnock: Its People and Townlands, A History, Fingal County Libraries.

Book of Leinsteir, part 150, accessed through https://celt.ucc.ie/published/G800011F/text152.html.

Branigan, Gary (2012), Ancient & Holy Wells of Dublin, Dublin.

Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language, accessed through http://edil.qub.ac.uk/.

Keating, Geoffrey, History of Ireland, Section XI, accessed through https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T100054/index.html

Kennedy, Tadhg (1984), The Velvet Strand, Ireland.

Life of Colman Son of Luachan, trans. Meyer, Kuno, accessed through https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T201036.html.

Placenames Database of Ireland, accessed through. https://www.logainm.ie/ga/

Schools’ manuscript collection, accessed through https://www.duchas.ie/en

Skyvova, Petra (2005), Fingallian Holy Wells, Fingal County Libraries.

[1] (Ahern 2013: 143)

[2] (Kennedy 1984: 43)

[3] (Keating, History of Ireland, Section XI)

[4] (http://edil.qub.ac.uk/14688 ; Book of Leinsteir, Part 150)

[5] (The Life Colman)

[6] (SC Vol 0932: 102; 236; SC Vol. 0932: 236; SC Vol 0624: 379; 441)

[7] (Ahern 2013: 151).

[8] (Logainm, https://www.logainm.ie/en/17028?s=portmarnock).

[9] (Ahern 2013: 143; Kennedy 1984: 31).

[10] (Kennedy 1984: 31)

[11] (Book of Leinsteir, section 150)

[12] (Adaman, Life of St. Columba: 117)

[13] (Ahern 2013: 149)

[14] (Ahern 2013: 149; Branigan 2012: 19; Kennedy 1984: 34; Skyvova 2005: 61)

[15] (Skyvova 2005: 61)

[16] (Ahern 2013: 150)

[17] (Branigan 2012: 20)

[18] (Skyvova 2005: 60)